Caring and Sharing; Roots and reminiscences of Scotland’s Gardens Scheme

by Juliet Edmonstone (2005)

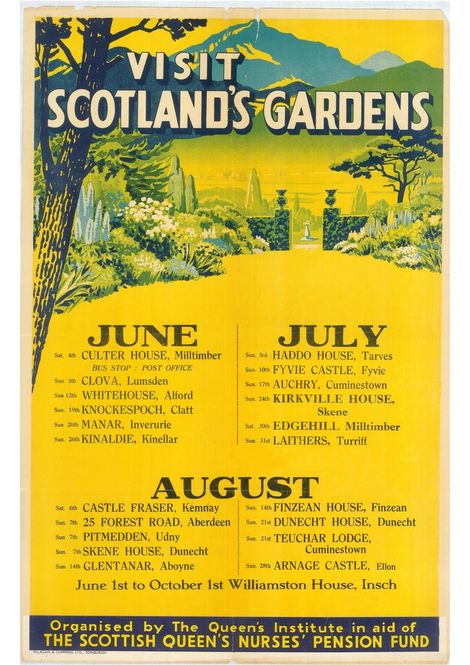

75 years ago, our wonderful SGS was born. A well-rooted hardy perennial if ever there was one and, like so many success stories, the right idea at the right time, for the right people. Instant popularity was ensured by this brilliant combination of horticulture and an enjoyable opportunity to admire the neighbour’s garden, whilst supporting the much-loved District Nurses. Following the example of HM King George V who immediately opened Balmoral gardens twice weekly, private owners threw open their gates too, responding enthusiastically to this new idea of sharing their gardens with appreciative visitors, all contributing to so worthy a cause!

It all began in 1931 following the success of the National Gardens Scheme. With the warm support of HRH The Duchess of York (later Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother), Violet Countess of Mar and Kellie (Chairman of the Scottish Queen’s Institute of District Nursing) gathered together the first SGS committee under the chairmanship of the Countess of Minto. Under her a network of County Organisers were appointed, who, though guided from above, ran their own area according to its needs – just as it is today. Much credit is due to the energy and personal commitment of these ladies and the successors who happily persuaded garden owners to open and ensured that the Scheme ran smoothly. Lady Rosebery, for instance, rescued a last-minute crisis by selling 2,000 daffodils in the streets of Edinburgh – a really most unusual sight for those days!

Most of those early gardens belonged to what one might call smart county families and opened on any day of the week – reflecting perhaps that the privileged and more leisured lifestyle afforded by these beautiful properties also brought with it a deep and traditional sense of public service. The example and goodwill of that generation lives on in the thousands of equally dedicated and public-spirited owners who support us today and in a much more hands-on way than in the past! Nowadays the Scheme welcomes some 350 gardens of every type imaginable, and valuable income also comes from dedicated National Trust for Scotland days, contributions from ‘ever-open gardens’, busy plant sales, and popular village openings.

The first yellow handbook of 1932 listed over 500 gardens in return for a ‘voluntary contribution’ and was really a simplified version of today's Guidebook. This surprisingly remained until 1962 when a charge of 1/- was made but the garden openings had dropped to 238. In 1971 the handbook burst into colour for 20p and became a forerunner of our present one.

Originally the idea was that the Scheme should contribute to the training and pensions of the Queen’s Nurses, but with the introduction of the NHS by Aneurin Bevan in 1948, their training became the responsibility of the Government. It was still essential, however, to contribute to pension funds of £1 a week for the 300 nurses who had not worked the requisite 15 years before retiring in order to become eligible, and also to help those in ‘necessitous circumstances’. There was, in addition, the nurses ‘holiday home’, Colinton Cottage, the Christmas Gift Fund and also projects out with NHS funding.

The Queen’s Institute of District Nursing grew out of the visionary efforts of William Rathbone, a Liverpool businessman. Concerned at the total lack of nursing care for the poor, he paid his wife’s nurse – a Mrs Robinson – and another nurse to go out into the community, where conditions of terrible deprivation had resulted from insufficient planning during the vast expansion of cities in the Industrial Revolution. There were, it seems, plenty of industrial entrepreneurs in those days but very few people with a social conscience. He then enlisted the help of Florence Nightingale and in 1862, established a nurses training school attached to Liverpool Royal Infirmary.

In 1887 Queen Victoria allocated £70,000 from her Jubilee gift from the ladies of Great Britain towards ‘Improved means of nursing for the sick poor’ and two years later the first of many training centres was set up in Edinburgh where nurses spent six months learning all the additional skills they would require out in the community. These ranged from budgeting to home hygiene, tuberculosis to cooking and were learned in order ‘to understand the difficulties and outlook of those with whom they would come into such intimate contact’. By 1927 every village in the country had its own Nurse and 65 years after William Rathbone’s inspirational lead, district nursing became an integral part of British life!

To understand these remarkable women, I can do no better than to quote from Isobel, Marchioness of Graham, the first General Organiser, whose eloquent reports and first-hand memories paint such a vivid picture of life not all that long ago. ‘Such were the standards, the understanding and the care given by a Queen’s Nurse’, Lady Graham wrote, ‘that she could penetrate districts – in her navy-blue uniform with its Queen’s badge and her little black bag of equipment – that no policeman could go alone’. They paid a high price for their devotion to the communities they served; ‘Long hours on call night and day, arduous treks by bicycle round back streets, up steep tenement stairs, across bleak moors and stormy seas in all weathers’.

As they put their knowledge and skill at the service of the sick, Queen’s Nurses became the trusted friend and confidante of their patients – chatting away as they washed them, made beds and aired the rooms. They were without doubt both saint and hero as we see only too vividly from a report sent back – probably around the turn of the century – by one of the early nurses to the Outer Hebrides. On her first confinement visit she is rowed to one of the islands and arrives drenched in sea water to find her landlady’s dwelling is a typical two room apartment with mud floors. One room she notes with horror is where they all sleep ‘regardless of age and sex’ and explains that this would make her ill! There are no cupboards or drawers, and the second room has only a kitchen fire in the middle and a smoke hole in the roof. There is little to cook anyway save mutton, herring, eggs, onion and potatoes. Even worse, there is virtually no fruit or even milk with which to make porridge. Her Christmas dinner is salt herring and baked sago and, not surprisingly, she is miserable and homesick, not helped by the fact that of course her patients only speak Gaelic! Despite it all, and with nobody to talk to, she writes, ‘I am happy in my work and my patients try to be kind to me. Poor souls, they have so little interest and nothing to be seen but water and hills’.

Another writes from a mining district that although she ‘has come to the last place on earth, it would be a real wrench to part from my people whose faces light up with welcome when one goes in and whose dull, hard lot one does brighten’. She speaks heart-warmingly of 16-year-old Janet struggling to look after five younger siblings after their mother’s death.

Far from being brought to a standstill by the war, the infant SGS flourished, although garden openings understandably dropped from 500 to 300 as gardeners left for the war, and some gardens were damaged and even destroyed by bombing. Proceeds, however, actually increased as, in true British spirit, garden owners tried to ignore the weeds and dug for victory by growing vegetables (for sale of course!) in the flower beds. Tea was patriotically served on the lawns… without sugar. Such was the esteem in which garden openings were held that extra petrol was allowed for special buses to bring visitors from the mines and factories (others came by bicycle, pram and even bath chair!) and owners were issued with special application forms for sufficient petrol to mow the lawn – once a month!

In 1942 Lady Graham’s garden was opened with a rousing speech by the Duchess of Roxburgh in which she spoke of the ‘comfort it was to the men and women of the forces to know that in times of trouble and sickness, the District Nurse was on call at all times of the day and night to the homes they had had to leave behind’, and a grateful visitor replied ‘I have enjoyed and seen more things this afternoon than anything in money could possibly repay’. I don’t think you can earn more praise than that, except possibly from the harassed official at Dundee bus station who, when asked for the Glamis queue, replied ‘Lady it’s not a queue, it’s an evacuation!’ In those days’ cakes were often provided by local bakeries and great was the excitement when ice-cream became legal again! Nowadays the QNIS, with our agreement, disburses the SGS funds to selected Scottish Community Nursing projects which help to raise standards of patient care, such as the development of Best Practice Statements and a CD Rom on Dementia for use by Community Nursing staff.

In 1952 and after much discussion on the merits of ‘rival suitors’, it was decided to appoint the Gardens Fund of the National Trust for Scotland (founded the same year as SGS mainly due to the inspiration of Sir John Stirling Maxwell of Pollock) as a second beneficiary.

In 1961 an important decision was taken to allow owners – if they chose – to allocate 40% of their gross takings (average £60) to a registered charity of their own choice. Altogether 170 different charities a year benefitted from this unique and popular arrangement. At the same time, it was agreed to make small annual disbursements to the Royal Gardeners Benevolent Fund (now Perennial) and The Royal Gardeners Orphan Fund.

That first year the Scheme raised £2,181 (including donations) and in 1932, which was the first full year, 577 gardens had more than doubled that figure to £5,400 – the equivalent today of £242,800. Records show that each decade after that more or less doubled the proceeds and during the 1980s annual income more than trebled to an incredible £178,700! The average return from each garden then was £250, which would be £493 today. By 2000 annual proceeds had leapt to £266,800 and in 2005 garden owners raised over £300,000 for the first time. Their choice of charities is an interesting reflection of modern thinking, ranging from the local village church to medical and cancer related charities, hospices and the many very personal choices of the owners. In 1982 SGS won the British Tourist Authority award for ‘Outstanding Contribution to Tourism’ and thus was recognised handsomely the contribution the Scheme makes to Scotland and its way of life.

SGS is lucky to have been organised and chaired by some very special personalities and I am most grateful to Sir Ilay Campbell of Succoth (our Vice-President) for his reminiscences of them during his many years of wise counsel on the Executive Committees of the National Trust for Scotland and ourselves. Lady Graham served as General Organiser for 23 years until 1953. ‘She was’, remembers Sir Ilay ‘an outstanding organiser who served four successive Chairmen and guided the boat through the choppy seas of the war years’. She also compiled meticulous lists of the takings from each garden and county which were circulated and publicised, possibly to encourage the merest – and most ladylike – hint of competition! Later, as County Organiser for Stirling, she became my friend and mentor who modestly hid her intelligence and efficiency. She was succeeded by Alice Maconochie who served for 19 years ‘Alice’s special brand of slightly caustic humour’ says Sir Ilay ‘will be recalled by all who worked with her – and none worked harder than she. All Scotland knew her and she knew all Scotland – rather too well for its liking!’

Poppy Davenport, who serve for 11 years and started the Garden Tours, will be ‘best remembered for her efficiency and humour’ and Mrs Moffat ‘for her smiling face and impeccable dress sense!’ Since 1982, Robin St. Clair-Ford has been our Director and his conscientious and fruitful commitment to the modernisation and image of the Scheme has achieved record results. His Garden Tours are conducted with customary cheerfulness!

The first Chairman, Marian, Countess of Minto was succeeded by the Duchess of Roxburghe and then by the Countess of Haddington before herself serving a second term. Sir Ilay admired greatly her ‘exceptional charm and organisational ability’. Mrs Alistair Balfour of Dawyck then took over. She was my first Chairman, and her charismatic personality left a lasting impression. Sir Ilay remembers her ‘unique blend of elegance and delightful wit.’ I remember her consummate skill in conducting a meeting – a lesson to us all. If anyone asked a stupid question, or one which she had no intention of answering, she would fix the offender with a fascinated expression, pause and murmur in a deep voice, honed to perfection by her broadcasting career, ‘how ….er…..interesting. Shall we move on’.

After 14 years she was succeeded by Lady Minto’s daughter-in-law, Minnie (also Lady Minto) – a charming and diligent American. Sir Ilay recalls her dedication and enthusiasm ‘Everyone was captivated by her fairy-tale princess looks and her honest to goodness niceness’. The Hon. Mrs Macnab of Macnab and I were her vice-chairmen, and I shall never forget the dignity with which she conducted herself during her last painful fight against cancer.

Minnie was succeeded by Diana whose energy and natural authority made her an excellent chairman. She was followed by the late Barbara Findlay who, despite serious ill health, devoted a great deal of time not only to the Scheme but also to visiting every garden she could. Barbara’s successor Kirsty Maxwell Stuart, with her practical, friendly nature and knowledge of plants, was an equally popular Chairman and Charlotte Hunt, also an experienced gardener, is now carrying the baton into the 21st century, liaising with other organisations and introducing new ideas with great success.

Together they, the District and County Organisers, Honorary Treasurers and other volunteers – without whose often-unsung efforts the Scheme would not exist – have forged the SGS of today. The Head Office is bursting with technology and our website and modernised handbook ensure that the maximum number of visitors can admire and learn from gardens large and small, traditional and modern. The enduring appeal of sharing and caring for our gardens and our charities is as robust and evergreen as it was 75 years ago!

© Juliet Edmonstone 2005

Find a Garden

Find a Garden

What's New

What's New

Our Impact

Our Impact

Join

Join